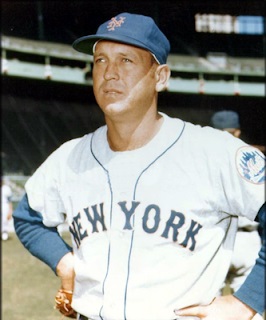

A new SABR biographic offers an excuse to remember the amazing Met for whom this journal is named.By Yours Truly

https://throneberryfields.com/2019/03/05/eight-million-new-yorkers-called-him-marvelous-marv/

Long enough after his baseball life ended, he carried a distinctive business card at the trucking company where he then worked in his native Tennessee. It was a foldover card, the inside of which showed his name, his contact information, and a once-familiar mug shot of himself in a Mets uniform. The top featured a trimmed oval cutout to show the mugshot below, an embossed sentence straight across the bottom saying it simply enough:

EIGHT MILLION NEW YORKERS CALLED HIM MARVELOUS MARV.

Marv Throneberry was the unlikeliest star on baseball’s unlikeliest team, after the Original Mets acquired him early in the 1962 season, becoming a Met in the first place because beloved Brooklyn veteran Gil Hodges went down with a knee injury, and the Mets were slightly desperate to put someone, anyone at first base with a blood count and a little long ball power who might be an improvement over anyone else on hand.

They had no clue that this once-glittering-enough Yankee prospect, who’d terrorised the AAA American Association with his home runs but couldn’t crack a Yankee lineup in which incumbent Moose Skowron owned first base with everything short of legal documents, would become so typical an Original Met that he’d replace the boos he got in his early days succeding Hodges to the kind of cheering the Beatles would inspire two years later.

“(B)ack then we were a more humorous and tolerant people,â€

wrote the

New York Times‘s George Vecsey, upon Throneberry’s death of cancer at 60 in 1994, “and there was room to enjoy a team that couldn’t help doing ghastly things, and the baldish, mournful-looking first baseman who seemed to perform more ghastly deeds than anybody else.†That’s the problem with today’s tankers. They have as much good humour as a tax examiner.

Throneberry wasn’t a born Met, if you don’t count the initials of his full name, Marvin Eugene Throneberry. To get him from the Orioles the Mets had to send them the proverbial player to be named later, who turned out to be—in a model of Metsian maladjustment—the actual first Met, catcher Hobie Landrith, whom the Mets took from the Giants with the first pick of the National League expansion draft that formed the team.

“The first thing you have to have is a catcher. Because if you don’t have a catcher, you’re going to have a lot of passed balls and you’re going to be chasing the ball back to the screen all day,†said manager Casey Stengel, explaining the Mets picking first and picking Landrith. “Thirty-one year old catcher who looked twenty-eight and played like forty,†wrote Leonard Shecter, in

Once Upon the Polo Grounds. “Hobie always said he was 5’8″. He probably was 5’6″. It wasn’t his fault he wasn’t big enough to play this game.†(

Baseball Reference lists Landrith, still alive at 88, as 5’10â€.)

Landrith was a perfect Original Met—until he wasn’t. On Opening Day he threw past second base trying to cut down a would-be base thief and committed three passed balls in 21 games. But earlier in May than the deal that brought Throneberry aboard, Landrith hit a game-ending two-run homer off Hall of Famer Warren Spahn. It was the first win in the Mets’ first doubleheader sweep. (The sweep also provided the first and last wins to Mets pitcher Craig Anderson, earning both in relief, before he experienced a streak of sixteen straight losses in sixteen straight decisions the rest of the season.)

Obviously Landrith had to go. He just didn’t have

quite what it took to animate the Original Met faithful. “The Mets were different, they were counterculture, they were fun,†Casey Stengel’s biographer Robert W. Creamer would remember. “The worse they were, the more fun they were.â€

Elder fans who returned to the Polo Grounds just because the National League was back in business at the Giants’ ancient but legendary wreck were supplanted readily by young fans for whom the Mets seemed far more human than the still-imperial, still-clueless Yankees. For the life of them the Bronx Bombers could never figure out why they almost got out-drawn at their stately coliseum by a newborn team who featured Abbott & Costello as a battery, the Four Marx Brothers covering the infield, the Three Stooges in the outfield, the Harlem Globetrotters on the bench, and the Keystone Kops in the bullpen.

And there was no more human Met than Throneberry, who’d gone from the Yankees to the Kansas City Athletics in the trade that made a Yankee out of Roger Maris. His flair for occasional dramatics showed up there, when he smashed a game-winning, pinch-hit grand slam to beat the Tigers one 1961 day, and drove in all the runs to beat the Twins on another. Except that the A’s had no place to put him regularly, either, and neither would the Orioles who acquired him in a postseason 1961 deal.

By the time the Mets got hold of him Throneberry was damaged goods, gone from a live teenage prospect to a 28-year-old semi-veteran who could swing the bat but whom rust reduced to playing either first base or right field as though he were impersonating a trash truck with two flat inner rear tires. “Marv Throneberry was holding down first base,†Jimmy Breslin wrote, in

Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? The Improbable Saga of the New York Mets’ First Year. “This is like saying Willie Sutton works at your bank.â€

Which was probably frustrating to a still-young man who’d once led the American Association in fielding percentage, but destiny had far bigger plans for Throneberry. Somehow, some way, and with more than a little help from his Hall of Fame teammate Richie Ashburn (who first gave him his to-be-famous nickname), and from Shecter (then a writer for the

New York Post, who took Ashburn’s sobriquet and ran with it), he became Marvelous Marv.

Ashburn took a special interest in the otherwise earnest Throneberry, using his wicked sense of humour to brace up his clubhouse locker partner. Around the same time, Throneberry began touching a real nerve among the younger Mets fans, the first sign being a literal sign, a banner hung from a Polo Grounds rail chanting, “Cranberry, Strawberry, We Love Throneberry.†Another group of young fans wore T-shirts spelling out “M-A-R-V†with the fifth showing an exclamation point; they once, famously, stood up in the wrong order, spelling out “V-R-A-M-!â€

I’ve written and said in the past that where other bad baseball teams merely suck, the Original Mets sucked . . . with

style. Throneberry was a style setter. You had only to see him in June 1962, on the same day during which Hall of Famer Lou Brock, then a Cubs rookie, jolted the Polo Grounds and his own teammates by blasting one into the center field bleachers some 465 feet from home plate. (Only two before him had ever hit one there: Joe Adcock with the Braves a decade earlier, and Luke Easter in a late 1940s Negro Leagues game.)

In the same game, Throneberry whacked one down the right field line and well past the bullpen for a standup triple, gunning it around the bases as if he had a subpoena on his trail. Then Hall of Famer Ernie Banks called for the ball and stepped on first, and Marvelous Marv was rung up. Before Stengel could consummate his mission to dismantle the first base umpire, coach Cookie Lavagetto intercepted him: “Forget it, Case, he didn’t touch second either.â€

“Well,†Stengel muttered, “I know he touched third because I can damn well see him standing on it.â€

The next Met batter, Charley Neal, ripped one off the facade of the upper deck for a home run. Neal wasn’t five steps up the first base line to run it out when Stengel stopped him cold. Then, the manager pointed to first base and stamped his foot. Only then did Neal continue running. Stengel pointed to each base and stamped his foot likewise, until Neal crossed the plate. The Ol’ Perfesser wasn’t taking chances.

Like the character actor lost among a sea of secondary cast who steals the scene and the show right before the final curtain, one day in the following month Throneberry pinch hit against the Cardinals in the bottom of the ninth and won the game with a two-run homer. And in August, he saw and raised in a somewhat surreal game against the Pirates.

Throneberry was actually on the first base coaching line, after third base coach Solly Hemus was ejected during an argument with an ump, Lavagetto was moved to coach third, and another former Yankee, Gene Woodling, also an acquisition from the Orioles, went out to coach first. Until Stengel needed him to pinch hit and sent Throneberry out to the coaching line. (To rapturous cheering, let the record show.)

Then the Mets scored one and had first and second with two out in the bottom of the ninth against the Pirates’ relief legend Elroy Face. The Polo Grounds faithful chanted “We want Marv! We want Marv!†Stengel gave the people what they wanted and Throneberry gave them better than that, hitting one 450 feet into the right center field seats for the game. The Polo Grounds went absolutely nuclear.

There was no less likely star in baseball, in New York or elsewhere, than this guy who looked like your friendly neighbourhood tavern barkeep, but 1962 was his first real and last ever baseball hurrah. After a 1963 contract holdout Throneberry found himself yet again having to buck others at first base, particularly two youths, acquisition Tim Harkness (from the Dodgers) and a teenager named Ed Kranepool, whom the Mets signed with a hefty bonus in 1962 right out of high school.

Marvelous Marv got only fourteen at-bats and two hits when he was sent to the Mets’ then-AAA farm at Buffalo. He stayed there for all 1963 but retired in early 1964—by which time the hundred-plus fan letters he’d once received per day was down to a reported two. (Now and then, during 1963, Polo Grounds fans would hang banners urging, “Bring back Marvelous Marv!â€) He returned to his native Tennessee and became a Memphis beer distributor before going into the trucking business, whence the business card described earlier.

But somehow, some way, he was unforgotten. In the 1970s he became famous all over again in the fabled Miller Lite commercials featuring former sports stars. Throneberry appeared amidst some of sports’ greats and mere legends, invariably ending his spots with, “I still don’t know why they asked me to do this commercial.â€

“At the very least,†Vecsey wrote, “it meant that one of the hip fans from the Polo Grounds had made it to Madison Avenue and was using his 1962 Met-type humor to honor Marvin Eugene Throneberry, who was, in his own weird way, a star.†Marvelous Marv was a star all over again.

Throneberry kept a photograph in his locker, well displayed, of a rather comely young lady in a bikini, and his teammates, including his setup man Ashburn, couldn’t help noticing and ogling, to Throneberry’s quiet amusement. Then, one afternoon, taking pre-game practise, Ashburn saw the woman sitting in the Wrigley Field field boxes. “Marv, you’ve got to see this,†Ashburn hollered to Throneberry.

Throneberry ambled over, and Ashburn pointed the woman out. “That’s the girl in your locker,†Ashburn said.

Throneberry grinned. “That’s my wife,†he said.

Ashburn’s jaw hit the turf promptly.

(Dixie Throneberry died in 1981; the Throneberrys had three daughters and two sons, with eleven grandchildren and fifteen great-grandchildren.)

“Throneberry is the people’s choice,†Ashburn once told Shecter, “and you know why? He typifies the Mets. He’s either great or terrible.†Throneberry happened to be standing next to him. “But you better not get too good,†Ashburn cracked. “Just drop a pop fly once in awhile.â€

Throneberry dropped his own jaw twice at season’s end. The first drop was over being given a big cabin-cruising boat because it turned out he hit the O on an outfield fence sign promoting Howard Clothes more than any other Met. It was bad enough that he lived about thirty miles from the nearest river at the time. The second jaw drop came when a Met legal adviser informed Throneberry he had to declare the boat on his income tax—because he’d “earned†the boat.

“You think the fish will come out of the water to boo me this winter?†Throneberry asked.

Not a chance. He had an occasionally powerful bat and a sense of humour about himself, and they took him places enough in life, including the sweet advertising gig where he earned more than baseball, beer distribution, or trucking ever paid him in a year, seemingly. He was a countercultural anti-hero before the counterculture became serious to a dangerous and conformist fault about itself.

“Going to work just two times a month and making a great living,†Throneberry once told the

Times of the Miller Lite spots and magazine ads. He’d also moved to the more waters-adjacent Fisherville, where his former major league brother Faye also lived. “I can fish four or five days a week. I’ve got five boats and five motors. I don’t have to worry about things I used to worry about. I wouldn’t trade this for anything.â€

Writing his story for the Society for American Baseball Research’s

Bio Project, which provided the excuse to write of him now, Alan Raylesberg exhumes a commentary from Throneberry’s oldest son, Jody:

He must have been special to have over 5000 fans wear shirts with VRAM on them. He truly loved his fans. I have watched him sit around hours on end and read fan mail and sign and return them to his fans. In the last days of his life when suffering from terminal cancer he would make it a point to sign as many cards as he could and have them mailed back out. That is the Marvelous Marv we all knew and loved.

And that’s also the Marvelous Marv for whom this journal happens to be named.

Marvelous Marv, one of the Miller

Marvelous Marv, one of the Miller

Lite All-Stars.-------------------

@Polly Ticks @Machiavelli @AllThatJazzZ @AmericanaPrime @Applewood @Bigun@catfish1957@corbe@Cyber Liberty@DCPatriot @dfwgator @Freya@GrouchoTex @Mom MD@musiclady@mystery-ak@Right_in_Virginia@Sanguine@skeeter@Skeptic@Slip18@SZonian @TomSea @truth_seeker