With the dubious three-batter minimum for pitchers due to arrive in 2020, let us celebrate the first truly hard-core single-batter relief specialist.By Yours Truly

https://throneberryfields.com/2019/03/14/bill-henry-patron-saint/ The patron saint of the single-hitter

The patron saint of the single-hitter

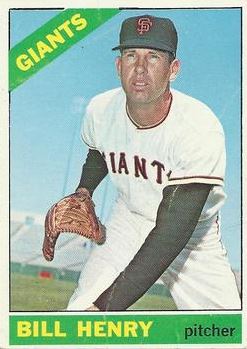

pitching specialist, on his 1966

baseball card.Baseball isn’t necessarily broken, but between them commissioner Rob Manfred and the players’ union have agreed to a few fixes. One of them is aimed at putting an end to the supposed rash of relief pitchers assigned to get rid of a single batter, starting next season.

Never mind that, as Jayson Stark

has exhumed, only one pitcher in 2018 had twenty or more assignments in which he was asked to get rid of a single hitter—now-former Mets reliever Jerry Blevins. Stark also unearthed that only five other pitchers last year (he didn’t identify them as I write) had fifteen or more single-batter assignments.

In essence, the single-batter relief pitcher doesn’t poke his nose out of his bullpen hole quite as often as you might think, lately, and as baseball’s hysterics would have you believe. Nor was it yet another creation of this supposedly wild and crazy 21st century in which the Sacred Game is rent this or that way by modernistic geek interlopers bent on keeping us up all night.

But the three-batter minimum, something I first thought seemed sound,

will have its major problems. Especially if a pitcher freshly installed doesn’t have his best and finds his first two batters slapping him silly, perhaps because he was gassed going in after being warmed up in the pen injudiciously or for too long before he was brought in (and that’s before the eight warmups on the mound), perhaps after coming in with men on base and a game on the line.

Fourteen years ago, a

Hardball Times writer named Steve Treder

sketched out a kind of history of the lefthanded one-out guy—known popularly by the LOOGY acronym—and traced it back to 1960 and the Kansas City Athletics. First, however, Treder offered a reasonable definition:

[H]e’s brought in to face, if not a single dangerous left-handed hitter, then at least a part of the lineup containing a key lefty, or two or more lefties. Very often this is in a fairly high-leverage game circumstance, rarely before the fifth or sixth inning. Sometimes LOOGYs are deployed in the ninth, but rarely are they used in Save situations. Very rarely are they left in for much more than a single inning.

LOOGYs are selected for the role primarily on the basis of their particular effectiveness against left-handed batters — or, to be less kind, on the basis of their particular ineffectiveness against right-handed batters. They’re often long and lanky types, with snaky sidewinding deliveries.

Treder defined such a pitching season as the specialist appearing in twenty games or more (hello, Mr. Blevins), fewer than 1.1 innings per gig, and lower than a twenty percent save situation factor. He prowled the data and discovered 799 pitching seasons within those coordinates through 2004, the first of which was delivered by Leo Kiely.

Kiely was a six-year veteran of the Red Sox bullpen before he was traded to the Indians (for a spare part named Ray Webster) in January 1960 and to the A’s (for former Yankee Rookie of the Year pitcher Bob Grim) in April of that year. Kiely was a soft-tossing junkballer who appeared in twenty games, pitched twenty and two-thirds innings, pitched as much to his defense as anything else, and showed a 1.74 earned run average for his effort.

Naturally, the A’s let him go in June 1960, and Kiely never appeared in the Show again. A wisenheimer might suggest he was simply too good at his job to fit the profile of that sad-sack team. But Kiely was the unlikely prototype of his breed. Two years later, three American League pitchers were given similar job descriptions and assignments: Dean Stone (White Sox, after coming in a trade with the Colt .45s), Bob Allen (a sophomore Indian), and Jack Spring (Angels).

Angels manager Bill Rigney made Spring the first multiple-season single-batter specialist when he gave Spring the same job in 1963. The type turned up here and there the next couple of seasons, but in mid-1965 the Reds traded a tall lefthanded reliever to the Giants and gave Giants manager Herman Franks an idea.

Franks belongs in the Hall of Infamy for his role in Leo Durocher’s then-high tech sign-stealing scheme that ignited the 1951 Giants’ pennant race comeback to force the three-game playoff. (Franks was the coach wielding utility infielder Hank Schenz’s Wollensak spyglass and buzzing the stolen signs to the bullpen where they’d be transmitted to the Giants hitters who wanted them.) But he also belongs in the Hall of Unlikely Innovation for what he did with Bill Henry.

Henry was the classic tall, quiet Texan who was so reserved his teammates nicknamed him Gabby and Jim Bouton, in

Ball Four, described Henry thus: “When you say hello to him, he’s stuck for an answer.â€

He’d been a key element in the 1961 Reds’ surprise pennant, teaming with their resident journalist Jim Brosnan to form a formidable enough one-two punch out of the pen. Now he was a 37-year-old veteran, with an effective curve ball and an equally sharp sinker and a facility for throwing double play balls, and after the Giants finished out a tight 1965 pennant race against the Dodgers, to which Henry contributed four saves, Franks decided to give him a new job.

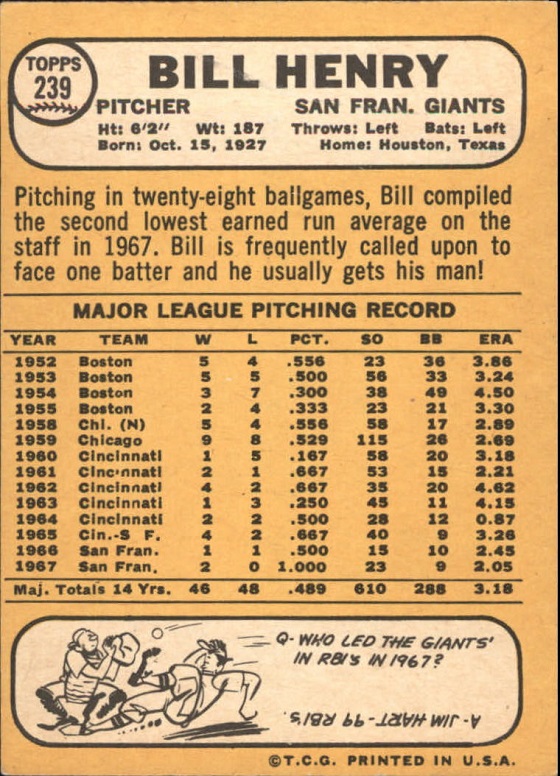

In 1966 and 1967, Henry pitched 43.2 innings in 63 games, with an ERA of 2.27 and a fielding-independent pitching rate at 3.50; Henry was better at taking care of business without his fielders in 1967. Arguably, Henry’s 1965-67 stretch with the Giants was the best three-season stretch of his long and quietly distinguished relief career. But the backside of his 1968 Topps baseball card said it all:

Henry began to show his age in 1968; he ended up spending that season between the Giants and the Pirates, to whom he was sold that June and from whom he was released two months later. The Astros signed him in May 1969; in June he pitched his final pair of major league gigs in both ends of a doubleheader: 2.1 scoreless in the opening loss; two scoreless in the winning nightcap.

Even with Henry’s success in San Francisco, it still took some time before the hard-core single-hitter pitching specialist took deeper hold than in his and the earlier years of the 1960s. And, to come not from the ranks of aging veterans or marginal prospects.

Ed Vende Berg was a Mariners lefthander who set a record for rookie appearances in 1982 (78) and who was as hard core those two seasons as Henry was with the Giants with more appearances than innings pitched. Vande Berg was also very effective in the role: his ERA for those two seasons was 2.87; his FIP was 3.33. “[H]e was a prime prospect out of Arizona State who had blown through the minors in a season and a half,†Treder wrote, “and been installed as a full-time LOOGY the moment he arrived in the majors.â€

Then, in 1984, the Mariners changed managers, from Rene Lachemann to Del Crandall, and Crandall made a mistake: he moved Vende Berg into the starting rotation. Vande Berg was out of his element as a starter and he was returned to the bullpen for one more LOOGY season that wasn’t as effective as his first two. He moved to the Dodgers in the deal that made a Dodger out of Steve Yeager; then, to the Indians and the Rangers, but he was never again the pitcher he was in his first two Seattle seasons.

By the time Vande Berg’s career ended, the single-batter specialist started taking further and further hold. There were 131 such seasons between 1960 and 1986, Treder noted, by once-familiar names as Paul Assenmacher, Danny Coombs, Ken Dayley, Joe Grzenda*, Al Hrabosky, Al Jackson, Jimmy Key (presumably before he became one of the American League’s premier starting pitchers), Paul Lindblad*, and John O’Donoghue.

But as Treder also noted, the hardest of the hard cores, Bill Henry’s grandchildren, began to turn up in the early 1990s, with Assenmacher, John Candelaria (once a promising starter), Jason Christiansen, Mike Holtz, Mike Myers, and Jesse Orosco (once a particularly effective closer). From 1987-2004 there were 191 single-batter pitching seasons to be seen.

Myers, who proved one of the bullpen keys to the 2004 Red Sox’s at-long-last return to the Promised Land, and who threw sidearm but looked like a telephone pole about to collapse as he threw, has the most such seasons of any of Bill Henry’s grandchildren: ten.

Henry himself finally called it a career in 1969. He stayed in the Houston area, raising his family and working as a longshoreman before retiring to a pleasant suburban life with his wife and surviving an unlikely amusement in 2007—when the paid obituary for a Bill Henry in Florida prompted a notice in the paper’s sports section the next day, which the wires picked up and spread until a Society for American Baseball Research writer got hold of the former pitcher to verify he was still alive and well . . . and dryly amused.

Henry also made a point of telephoning the man’s widow, who’d been smothered with phone calls when it was believed her husband was one and the same as the former relief pitcher. “He wasn’t really upset about it,†his daughter-in-law once told a reporter. “He kind of laughed about it.â€

The quiet man did have his moments, though. Jim Brosnan, writing in

Pennant Race, told a story about an 18 April 1961 game against the Giants, with the Giants’ Mike McCormick and the Reds’ Jim O’Toole having a pitcher’s duel, and the bullpen looking to amuse themselves with a few whacky bets, when spare part Hal Bevan finally challenged: “There’s too damn much noise down here. A guy can’t even think.â€

He suggested himself, Brosnan, and catcher Jerry Zimmermann clam up. Brosnan takes it from there:

I was more than willing. Conversation sharpens the ache of a hangover. “First guy to say anything buys the beer after the game,†I said.

Silence reigned. Uneasily. “Gabby†Henry wouldn’t join the bet and it amazed me how loud his few comments on life and the game could sound.

Late in the game, a fly ball was hit toward us. Harvey Kuenn, playing right field for the Giants, came running for it. Apparently Kuenn was going to have to run right into the wall to get the ball, but no word of warning was sounded. The ball drifted back into the field and Kuenn, stumbling in front of our bench, caught it.

“Christ, let a guy know somethin’!†he yelled at us. No one said a word.

“That’s sickening!†said Henry, shaking his head. “You three guys’d let a man get killed just so you could win a bet!â€

Three grinning faces nodded in agreement.

Henry himself died of heart trouble seven years later after he’d had to affirm that the report of his death was somewhat exaggerated. He pitched quietly, lived quietly, seems to have been loved and respected by anyone who knew him. And he was the hard-core patron saint of the single-batter pitching specialist today’s baseball fan thinks was a 21st century plot to overthrow the great and glorious game, and today’s baseball governors think need to be retired somewhat permanently.

-----------------------------------------------------

*

Joe Grzenda and Paul Lindblad hold a curious and sad place in baseball history: Grzenda was trying to save a win for Lindblad in the final home game in Washington Senators history. He never got to finish the save.

With the Senators leading 7-5 and two outs, Grzenda never got to pitch to the Yankees’ Horace Clarke. Heartsick fans exploded onto the field to vandalise it for souvenirs and, perhaps, outrage over the team leaving for Texas. The umpires declared a forfeit to the Yankees.

Over three decades later, when the Montreal Expos moved to Washington to become the Nationals, Grzenda was invited to throw out a ceremonial first pitch—and he did it with the ball he saved from that final Senators game, the ball he would have pitched to Clarke if not for the fan riot.-----------------------

@Polly Ticks @Machiavelli @AllThatJazzZ @AmericanaPrime @Applewood @Bigun @catfish1957 @corbe@Cyber Liberty@DCPatriot@dfwgator@Freya@GrouchoTex@Mom MD@musiclady@mystery-ak @Right_in_Virginia @Sanguine@skeeter@Skeptic@Slip18 @TomSea @truth_seeker