. . . to read Joe Posnanski's lyrical ballad from the American road with Buck O'Neil. By Yours Truly

https://throneberryfields.com/2020/08/04/its-never-too-late/

When you argue

as I have on behalf of putting an end to baseball’s (and all sports’) goat business, part of the argument is that to err is human, though not all err before audiences of millions on television and 55,000+ at the ballpark. The trouble is that most of us forget the part about forgiveness being divine.

Buck O’Neil, Negro Leagues legend and the first African-American coach in Show history, had enough to say about forgiveness to make a book in its own right. (He’d written one himself, his memoir

I Was Right on Time.) But there’s one story above all that’s going to stick with me for the rest of a life in which I’ve had to re-learn forgiveness repeatedly.

Watching a game with O’Neil in Houston, a writer saw a man and a boy, strangers to each other, stretch for a ball tossed into the stands by an Astros outfielder named Jason Lane. The man being taller, he caught the ball, then celebrated the catch. The boy looked absolutely crestfallen.

The writer quietly denounced the man as a jerk. O’Neil counseled him gently, “Don’t be so hard on him. He might have a kid of his own at home.†The writer, admitting he’d learned to try seeing things through O’Neil’s eyes, thought about it. Then, he asked, “Wait a minute. If this jerk has a kid, why didn’t he bring the kid to the ball game?†Smiling, O’Neil replied, “Maybe his child is sick.â€

The writer was Joe Posnanski, now a senior writer for

The Athletic but then a columnist for the

Kansas City Star. Their travels together delivered

The Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip Through Buck O’Neil’s America, published the year following O’Neil’s death at 94.

If you haven’t read it yet—as I hadn’t, until this week—put baseball’s Hitchcockian coronavirus season to one side and buy it. Read it. What began when O’Neil asked Posnanski how he fell in love with baseball became maybe the single most lyrical epic ballad ever written about one man’s love affair with a game that didn’t always treat O’Neil and his fellow Negro Leaguers, legends and scrubs alike, with the same love.

What Pete Rose merely thinks he’s been, O’Neil really was: baseball’s possible greatest ambassador, from the moment Ken Burns reached him to speak of the Negro Leagues generations for Burns’s mid-1990s documentary series,

Baseball. From there, O’Neil spread the words, the stories, the achievements of the Negro Leagues as if anointed by the God in whom he believed deeply to be that messenger.

Other baseball legends taking their stories on the road win fans. O’Neil made friends. But God wouldn’t have had to do anything more than just nudge the line drive-hitting, longtime Kansas City Monarchs first baseman turned manager. (Among others, he played with and managed Hall of Famer and colour line breaker Jackie Robinson.) Getting Buck O’Neil to shut up about baseball, Negro Leagues and otherwise, would have been like taking the alto saxophone out of

Charlie Parker‘s mouth.

If you think that’s a stretch, be advised or reminded that the only thing that ever animated O’Neil more than baseball was jazz. This sunny man who meant every word when he said nothing in his experience could ever force him to hate any human being of any colour once said, in Posnanski’s earshot, answering whether he had fun playing baseball when black men such as him were barred from the Show, “People feel sorry for me. Man, I heard Charlie Parker!â€

O’Neil’s passion for music equaled that for baseball, and he linked them unapologetically.

Music can’t be racist. I don’t care what. It’s like baseball. Baseball is not racist. Were there racist ballplayers? Of course. The mediocre ones . . . They were worried about their jobs. They knew that when black players started getting into the major leagues, they would go, and they were scared.

But we never had any trouble with the real baseball players. The great players. No, to them it was all about one thing. Can he play? That was it. Can he play?

“For five seasons,†Posnanski wrote, meaning nature’s and not baseball’s, “I would watch Buck look at the bright side. He had every reason to feel cheated by life and time—he had been denied so many things, in and out of baseball, because of what he called ‘my beautiful tan.’ Yet his optimism never failed him. Hope never left him. He always found good in people.â€

Part of O’Neil’s reason for going on the road with Posnanski was knowing he wouldn’t write just another clinical analysis of Negro Leagues baseball. “The books . . . mostly read like encyclopedias,†Posnanski wrote, “and that was no way to get people interested.†O’Neil put it more directly: “Somebody needs to write that book—the one that tells what it was really like. You’ll do it.â€

Poring through the morgues of the old black American newspapers such as the

Pittsburgh Courier and the

Chicago Defender wasn’t enough. Interviewing O’Neil’s fellow living former Negro Leaguers wasn’t enough. Then O’Neil mentioned an appearance in Nicodemus, Kansas, one of O’Neil’s inumerable stops to promote Negro Leagues baseball and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Posnanski asked to join him. “Be on time,†O’Neil replied.

O’Neil asked Posnanski inumerable questions instead of the writer doing the questioning. From there was birthed a portrait of an elder gentleman who wanted the world to know and remember just how good, exciting, and even transcendent Negro Leagues baseball, and those who played it before the disgraceful colour line broke, could be and usually were. And, its role helping America try to grow up in due course.

He was a player/manager for the Monarchs in the final decade of their existence and the Negro Leagues’s existence. As the Monarchs’ manager and then a Cubs coach, O’Neil could (and did) claim to have turned Hall of Famer Ernie Banks from a shy kid to the effervescent icon for whom every day was beautiful enough to play two.

“I learned how to play the game from Buck O’Neil,†Banks would say. Buck said no, Ernie Banks knew how to play, but what he did learn was how to play the game with love.

If he missed becoming one of the infamous Cubs’ experiment of rotating leaders known as the College of Coaches because of his race, since black men weren’t thought managerial material still in the 1960s, O’Neil also missed being remembered as a cog in a laughing-stock experiment that didn’t change the Cubs’ losing ways. As a major league scout before and after his coaching days, O’Neil’s finds included Hall of Famer Lou Brock and, in due course, 1993 World Series winner Joe Carter.

When seventeen Negro Leagues figures were elected to the Hall of Fame by the Committee on African-American Baseball in 2006—including Effa Manley, the longtime co-owner of the Newark Eagles—O’Neil was on the same ballot but missed election by two votes. He would have been the only living person in the group if he’d made it. We can only marvel at what his induction speech might have been.

The country that once enabled his and dozens of his peers’ exclusion from the Show now wept that this soulful, effervescent, accessible man would see Cooperstown only as a visitor or guest. I’m not ashamed to say I was one of them. From the moment I saw O’Neil on Burns’s

Baseball, my lone regret about the man is that I never had the honour of meeting him.

If O’Neil’s actual playing record isn’t as glittering as those of Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Monte Irvin, or Double Duty Radcliffe (Radcliffe died over a year before O’Neil), marry it to his self-appointed ambassadorship and his work on behalf the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and you should have had a Hall of Famer.

Speculation ran rampant that O’Neil’s exclusion

rooted in a feud between the impossible-to-dislike O’Neil and Larry Lester, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum’s original research director, who’d battled with O’Neil—who’d been the museum’s chairman and face—over policy issues.

The winners included Eagles legend Biz Mackey, who managed them to the 1946 Negro Leagues World Series championship (future Show Hall of Famer Roy Campanella was his catcher) and Cum Posey, the longtime owner of the Homestead Grays. And, Willard Brown, an O’Neil teammate on the Monarchs who owned a pocketful of Negro National League home run titles and became the first black player to homer (off Hall of Famer Hal Newhouser) in the American League. (It was Brown’s only major league homer.)

Characteristically, O’Neil could only bear to look on the bright side. This son of a Florida whose segregation included denying him high school in his youth saw his mere presence on the ballot at all as a sign America was growing up and getting better all the time, even if the growing pains remain profound. “I was on the ballot, man! I was on the ballot!â€

God’s been good to me. They didn’t think Buck was good enough to be in the Hall of Fame. That’s the way they thought about it and that’s the way it is, so we’re going to live with that. Now, if I’m a Hall of Famer for you, that’s all right with me. Just keep loving old Buck. Don’t weep for Buck. No, man, be happy, be thankful.

Graciously, O’Neil accepted the Hall of Fame’s invitation to introduce those seventeen new Hall of Famers. His speech was as memorable for its affection as for its evocation of living history, not to mention his getting everyone present, from the Hall of Famers on the podium to the crowd of all colours holding hands and singing a line from his favourite gospel song:

The greatest thing in all my life is loving you.

O’Neil had humane ways of putting in their place people who only think they know the “way it was†in his generation. “I wondered,†Posnanski wrote. “What did they know about his day?â€

They knew nothing about riding from one dot on the map to the next—one town named for a former president to one named for an old explorer—and playing baseball on dusty infields against furious dreamers on town teams. They were not there when Buck worked for the post office during the winters, and when he stepped outside for his five-minute break, he would smoke a cigarette, close his eyes against the chill, and think of sun and grass and spring training. And yet Buck never stopped them. He gently corrected them . . .

“I remember catching batting-practise home runs,†[a television reporter] said. “That was when baseball was still baseball.â€

“I don’t mean to interrupt,†Buck O’Neil said, “but baseball is still baseball.â€

Posnanski cited a verse fashioned out of one of O’Neil’s recollections about those Negro Leagues years, when the men who played the Negro Leagues game could only fantasise about being allowed to play with and against white men to whom they felt at least equal in talent if not yet in station.

People used to tell me

How they thought it was

Way back then.

Used to tell me

How they imagined it.

And I tried to say

It wasn’t like that.

We were men

Flesh and blood

And we played baseball in the sunshine.

We hit doubles off the wall,

Slid hard into second base.

We had fights, and we made love.

We sang songs and prayed on Sundays.

Before games.

We were real. Yeah. We laughed and cried.

There was a lot wrong with the world.

But we weren’t sad, man.

We had the times of our lives.

I told them that for fifty years.

They heard. But they didn’t listen.

They listened. But they didn’t hear.

When Posnanski asked O’Neil to identify his greatest day, ever (“I’d heard him tell it a hundred times. I wanted to know if he was awakeâ€), the old first baseman/manager/coach/scout didn’t flinch. Easter Sunday, 1943, in Memphis. The Monarchs played the Memphis Red Sox. O’Neil hit for the cycle. In his hotel later that evening, a friend introduced him to some local schoolteachers.

“I walked downstairs and walked right up to one of those teachers. I said, ‘My name’s Buck O’Neil, what’s yours?’ That was Ora. And we were married for fifty-one years. Easter Sunday, 1943. I hit for the cycle and met my Ora.â€

O’Neil’s only regret was that his baseball life kept him from his Ora far too often. She died eight years before her husband did. After you read

The Soul of Baseball, you’ll believe more powerfully that they were reunited serenely and happily in the Elysian Fields, where she grins as he reminds those who preceded him how to see the good through the bad, the beauty on the other side of the dark side.

You’ll also believe that Ora O’Neil—as should we who remain on earth, where he made America make him its friend—just keeps on loving Old Buck, as he keeps loving her and the game to which he gave more than it deserved.

If it’s never too late to read and recommend such a lyrical ballad to a man who was a gift to a country that didn’t always appreciate him and his generation, then Posnanski made one of my baseball wishes come true. I’ve finally met and gotten to know Buck O’Neil.

-------------------------

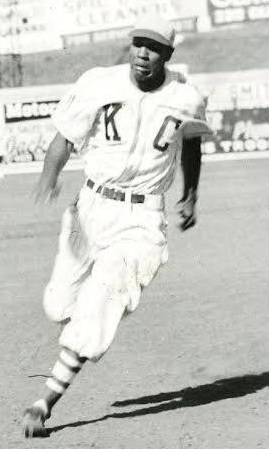

Buck O’Neil running the bases

Buck O’Neil running the bases

for the Monarchs: “I wasn’t no

power hitter. I hit those line drives.â€-------------------------

@Polly Ticks @AmericanaPrime @andy58-in-nh @Applewood @catfish1957 @corbe @Cyber Liberty @DCPatriot @dfwgator @EdJames @Gefn@goatprairie@The Ghost

@GrouchoTex @Jazzhead@jmyrlefuller@Mom MD@musiclady@mystery-ak@Right_in_Virginia @Sanguine@skeeter @Skeptic @Slip18@Suppressed@SZonian@truth_seeker