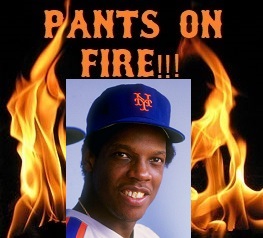

Sorry, New York Daily News: trying to fix what wasn't broken thwarted Gooden as a pitcher.By Yours Truly

https://throneberryfields.com/2019/07/12/goodens-pitching-ruin-wasnt-drugs/ The Mets tried to fix a Dwight Gooden

The Mets tried to fix a Dwight Gooden

that wasn’t broken. That’s why he was

never the same pitcher starting in 1986.Haunted and periodically haunting Mets legend Dwight Gooden incurred a June arrest for cocaine possession in New Jersey. The

New York Daily News,

revealing the arrest Friday morning, leads thus: “Fallen fireball pitcher Dwight Gooden, whose drug woes drove him out of a Hall of Fame career, was in trouble with the law again after a recent arrest on cocaine possession, according to court documents.â€

Emphasis added, unapologetically. The myth of Gooden’s drug issues driving him out of a might-have-been Hall of Fame career was debunked long before the

News‘s lede. Unfortunately, drug issues make for more bristling and enthusiastic water cooler and (today) social media talk than things like, you know, fixing what isn’t broken.

So here we go yet again. Read this very carefully. Drugs didn’t compromise Dwight Gooden’s pitching; the Mets monkeying around with a young pitcher who might have been a little overworked but still owned the game in his first two seasons and knew what he was doing on the mound did.

It’s not that Gooden was immune to dabbling with cocaine, beer, or other such substances even in his first two major league seasons, never mind before the infamous drug test failure that got him starting 1987 in the Smithers Institute. But let’s hark back to spring training 1986, and where Dwight Gooden actually was entering that spring.

He was the National League’s Rookie of the Year in 1984 (he smashed the rookie season strikeout record once held by Herb Score, with 276) and the pitching Triple Crown winner (24 wins, 268 strikeouts, 1.53 ERA) in 1985, the year he also won the National League’s Cy Young Award. His 2.13 fielding-independent pitching (FIP) led the majors (as had his 1.69 in 1984), so it seems a little of his winning was as dependent on his team as on himself. (His Show-leading ERA+: 229, 129 better than the average.)

Any way you see it, Gooden was major league baseball’s no questions asked best pitcher in his first two seasons. He did it with a four-seam fastball and the most voluptuous curve ball the National League saw since Sandy Koufax. (In those days a curve ball’s usual nickname was Uncle Charlie; Gooden’s became known as Lord Charles.) That’s all he had; it was all he needed. And with that .201 batting average against him,

nobody could hit him.

“I never got to play behind Bob Gibson or Sandy Koufax, but this was the equivalent,†then-Mets first baseman Keith Hernandez, now a Mets broadcaster, once said. “Gibson, Koufax, Gooden . . . legends, true greats. Dwight was in that class. He was so good that year that if he didn’t strike out ten batters we would joke around, ‘Hey, what’s wrong?’ You expected greatness every start. It was something to see.â€

“Every game,†Gooden would come to remember of 1985, especially, “I could put the ball where I wanted it.â€

But in spring 1986 and someone in the Mets’ brain trust decided despite the evidence that it just wasn’t enough. It might have been the late Mel Stottlemyre, the pitching coach, whose reputation was that of a gentleman and a gentle man who preferred to teach quietly and not rant and rave as many pitching coaches did in his own pitching days. Jeff Pearlman (in

The Bad Guys Won!) observed Stottlemyre viz Gooden thus: “Throughout (1985) Stottlemyre would watch Gooden perform and think,

Boy, this kid is amazing, and all he throws is fastball-curveball! Imagine if he had another pitch. That’s what he set out to do—teach the best pitcher in baseball how to be even better.â€

Except that, if that was right, then Stottlemyre missed his mark this time. “All through (spring 1986) Stottlemyre had Gooden toy with a changeup and a two-seam fastball, two pitches he did not throw,†Pearlman wrote. “It was hard to watch. Gooden was a trouper, but the confidence he exuded on his fastball and curve ball never attached itself to the other pitches. He felt awkward and unsure.â€

The spring 1986 Mets had four catchers in camp: Hall of Famer Gary Carter, the number one man, plus backups Ed Hearn, Barry Lyons, and future major league manager John Gibbons. And one and all of them thought Stottlemyre and others made a huge mistake.

Hearn: “I remember catching him one day in the bullpen and they were working with him on the two-seam. I’m thinking,

What the hell is this? He was a power pitcher with tons of movement, and they’re trying to teach him

movement? What the hell for?â€

Carter, who came to the Mets for 1985 and caught all but three of Gooden’s 1985 starts: “I always thought they should have left Doc alone. Mel thought teaching him a third pitch would be to his advantage. But he didn’t need it. He needed someone to say, ‘Hey, you’ve been successful. Just keep going at it.’ But they didn’t’. I also think it hurt his shoulder. The pitches didn’t feel natural to Doc, and pitching was so natural to him. It just wasn’t smart.â€

The Mets’ general manager at the time, Frank Cashen, urged Gooden to shorten his elegant motion and leg kick to make it harder for opponents to steal on him. (Gooden’s

one flaw then was that that naturally elegant windup, kick, and delivery were a little easy to steal on—if you reached base against him at all, that is.)

Cashen’s assistant GM, Joe McIlvane, who’d once pitched in the minors, urged Gooden against striking out the world the way he’d done in 1984 and 1985. Pearlman cites McIlvane telling manager Davey Johnson, “If we can reduce Doc’s pitches, we can save his arm. He doesn’t need 200 strikeouts to succeed.â€

As things turned out, exactly 200 strikeouts was what Gooden would deliver in 1986, as well as a 2.84 ERA but a 3.06 FIP, not to mention the opposition on-base percentage jumping 24 points higher in 1986 (.278) than it was in 1985. (.254.)

In one way, it was Gooden’s own fault. But only one. He was known to be pliant and accommodating, so much so that the Mets had to intervene to curtail some of his agreements to appear for this interview or that function before he was plain worn out. And pliant and accommodating when it came to his pitching coach and team overseers meant one thing. “In the pursuit of excellence,†Pearlman concluded, “Gooden made a tremendous mistake. He listened to everyone.â€

All that is

really what thwarted Dwight Gooden. For his first two major league seasons, he was Hall of Fame great and beyond. For the rest of his career, he was a

good pitcher who brushed with greatness every now and then (including his no-hitter as a Yankee), but he was no longer the pitcher about whom no less than Hall of Famer Koufax said, “I’d rather have his future than my past.â€

Brooklyn Dodgers manager Charlie Dressen made the same mistake with his own Rookie of the Year relief pitcher Joe Black in spring 1953. Black had posted a great rookie season that included becoming the first black pitcher credited with a win in a World Series game. Black had a hard fastball and a curve ball he threw more as a change of pace, but he knew what he was doing on the mound, too, and he made it work.

In spring 1953 Dressen anticipated the Dwight Gooden unmaking by decided Black needed “more stuff.†He forced Black to try throwing a bigger-breaking curve and possibly a forkball, pitches Black’s hand was physically incapable of gripping properly. But Black tried anyway: “Man says I got to try, I got to.†Uh-oh. Like Gooden in due course, Black’s confidence ended up shot. Unlike Gooden, so was Black’s control.

Gooden managed to forge a sixteen-season career that—despite his coming shoulder issues and his continuing struggle with cocaine and drink—still left him, at this writing, as the 97th best starting pitcher of all time. Black may have been lucky to last six major league seasons after Dressen’s wreckage. After pitching, Black became a Senators scout, then a high school teacher, and then an executive for Greyhound.

And, then, along came Gooden—who’s worked in and out of baseball since, and who continues struggling with the addictions that have pockmarked and potholed his life since—to bump Black to one side as one of New York baseball’s saddest, coaching-ruined might-have-beens.

“Had New York’s [1986] decision makers been present in 1506 when Leonardo da Vinci was painting the

Mona Lisa,†Pearlman wrote, “they would have insisted on a mustache and larger ears. Here they had Gooden, called ‘the most dominant young pitcher since Walter Johnson’ by

Sports Illustrated, and it wasn’t good enough.â€

Figure that if you can: The 1986 Mets were one of the greatest teams in baseball history and they opened the season by ruining theirs and baseball’s best pitcher of 1984-85. It turned out to be the prelude toward the gradual dismantling of a team that was supposed to stay great after returning to competitiveness in 1984 and winning the ’86 Series, but didn’t.

The rubble came from one after another deal that either rid the team of what Gooden himself called “the guys who used to snap†or drained the farm for modest, fading, or indifferent veterans.

And the once-glittering, slender fellow with the big wide smile, the becalmed manner, the pitching rhythm as elegant as Duke Ellington’s jazz, and the strikeout virtuosity that earned him the nickname Dr. K., remains living, breathing evidence of what happens when you call the repairman to fix what wasn’t broken in the first place.

Gooden with Hall of Fame catcher Gary

Gooden with Hall of Fame catcher Gary

Carter: Carter knew a big mistake was made

with The Doctor in spring 1986.--------------

@Polly Ticks@AmericanaPrime @Applewood @andy58-in-nh @catfish1957 @corbe@Cyber Liberty@DCPatriot @dfwgator@EdJames @Freya

@goatprairie @GrouchoTex @Mom MD@musiclady @mystery-ak @Right_in_Virginia @Sanguine @skeeter@Skeptic@Slip18@Suppressed @SZonian @TomSea @truth_seeker