Tony Gwynn and Ted Williams were friends. And batted six points apart lifetime. But who was really better?By Yours Truly

https://throneberryfields.com/2019/02/16/just-between-friends-captain-video-vs-teddy-ballgame/ Hall of Famers Tony Gwynn and Ted Williams, a couple of

Hall of Famers Tony Gwynn and Ted Williams, a couple of

southern California kids who were, as Casey Stengel might

have said, rather splendid in their line of work.The best argument I’ve ever seen on behalf of baseball statistical analysis came from Allen Barra, in the introduction to

Clearing the Bases: The Greatest Baseball Debates of the Last Century, published in 2002:

I believe in statistics. I do not trust people who say they do not. Whether it was Benjamin Disraeli or Mark Twain or whoever who said, “There are two kinds of lies, damned lies and statistics,†he was trying to pull the wool over someone’s eyes. Well, no, I take that back; I can see how someone would feel that way, particularly in regard to the manipulation of statistics, but this is not an argument against damned statistics, it is an argument against damned liars. How in the world any baseball fan can say that he doesn’t trust statistics is beyond me; stats are the life blood of the sport. No matter how many games you watch you can only see a tiny fraction of the games played; if you can’t trust numbers to tell you what happened when you weren’t there, then what can you trust?

For the record, Mark Twain popularised “There are two kinds of lies, damned lies and statistics,†but he attributed the phrase to Benjamin Disraeli. Anyway, the worst argument against statistics? I’d have a hard time picking one, but you’d probably find most of those in arguments about who does or doesn’t belong in the Hall of Fame, or arguments about who did or didn’t deserve to win certain seasonal awards.

As for the worst argument one way or the other about comparing players statistically, I thought most surrealism was exhausted until I bumped into one that put two Hall of Famers, Ted Williams and Tony Gwynn, into the same conversation, with the litigant in question suggesting Gwynn and Williams the two best pure hitters he’d seen in his lifetime. Said litigant is a friend of decent and long enough standing, though I fear our little tiff may have compromised that friendship, after I joined the discussion and suggested it was more than a little foolish to put Gwynn and Williams in the same conversation.

I tripped on my own banana peel. I hadn’t meant to suggest

he was a fool

himself, and I was (and still am) genuinely sorry that he thought I had. As I said subsequently (to someone who called me out on the inadvertent suggestion), I knew only too well the most intelligent men and women on earth could make a foolish suggestion now and then. (I didn’t have the heart to say that you have only to prowl assorted writings about our politics today to know how many intelligent men and women make how many foolish arguments.) But I’d forgotten for long enough that, when it comes to particular subjects and particular sensibilities, there’s no such thing as an unexposed nerve, even (I say it with no pride) my own.

In some ways, Tony Gwynn and Ted Williams do belong in the same conversation. They both hailed from southern California. They both belong in the Hall of Fame, they were both first-ballot Hall of Famers, even if it is rather astonishing to think that thirteen voters left Gwynn off their ballots, even as it’s slightly more astonishing to know that Williams received a lower percentage of the vote in his election year than Gwynn did in his. They both played their entire careers for a single team, which is more of a comparative rarity than people think. They were both predominantly number three hitters in the lineup. Their lifetime batting averages are six points apart: Williams hit .344; Gwynn hit .338. And they struck up a friendship of sorts during Williams’s final decade of life.

If that was

all you considered about the pair, you just might think they’re as close to a match as you can get, and there

are those who cling stubbornly enough to batting averages as the

alpha and

omega of a player’s value. With that stubbornness of course you’d look at Williams hitting .344 and Gwynn hitting .338 and, exploring no further, say to yourself that boy those two guys were about as close a match as you could imagine. But those close batting averages also provoke a reasonable question: how valuable

were they,

really, to their teams? What

did those gaudy batting averages bring to the party aside from the frequency with which they hit? How valuable

were their hits? What and how much did they

really do toward putting more runs on the scoreboard? (Stop snarling, old schoolers. Putting more runs on the board than the other guys, and making sure they put less runs on the board, is the name of the game.)

That’s what we should want to know if we’re going to have a conversation that marries Tony Gwynn to Ted Williams. And if that’s the case, the marriage needs to be stopped before it heads to divorce court.

Williams played nineteen major league seasons and Gwynn played twenty. Williams at this writing holds the highest on-base percentage of any player who played the game in any era, .482, and he played the bulk of his career in a game that ended its self-imposed talent segregation and shifted into the era of nighttime baseball. (That the Red Sox were the last major league team to admit a black player to its ranks wasn’t Williams’s fault.) Gwynn, whose era was more fully talent integrated and who played at least half his games at night, has a .388 on-base percentage. That’s the 111th best OBP of all time, and it’s almost a

hundred points lower than Williams’s. How did that happen when the two only hit six points apart with one season’s difference between their careers?

Gwynn was a tougher man to strike out than Williams, with 275 fewer lifetime, and Williams was tough enough to strike out. (Gwynn averaged 29 strikeouts per 162 games to Williams’s 50, and neither man

ever struck out in triple digits in any season.) But Williams was better at working out walks. Gwynn walked 790 times in his career and averaged 52 walks per 162 games. Williams walked

2,021 times in his career and averaged

143 walks per 162 games. That put Williams fourth all time (and you thought eleventh-place Eddie Yost was the Walking Man?) and Gwynn, 272nd place, tied with Joe DiMaggio. Williams also received 243 intentional walks, good for eighth on the all-time list, while Gwynn is seventeenth on the list with 203. You can argue plausibly that the each man faced a different caliber of pitching, but it still seems objectively that pitchers feared Williams at the plate considerably more.

Williams was better at avoiding double plays. In nineteen seasons, Williams hit into 197 double plays; in twenty seasons, Gwynn hit into 259. This is a little astonishing considering that by all indications Gwynn was the faster man out of the box and on the bases. (His stolen base percentage is .718 to Williams’s .585).

Williams, of course, was one whale of a power hitter; he was fourth on the all-time home run list when he retired with 521. Gwynn had some power but was a guppy compared to Williams, hitting 135. Today’s obsession with launch angling, and hitters focused primarily on that to the detriment of other hitting, leaves the home run a little devalued in a lot of fan minds now. But the home run isn’t going to disappear, even if you’d like a better balance between the big blast, some well-struck line drives into the gaps, and some roach-and-roll small ball. (And, while we’re at it, a lot more hitters looking at the rash of overshifts against them and deciding those creamy open spaces they’re being gifted are the perfect places to send some base hits.) The launch anglers who hurt themselves otherwise with the obsession could stop worrying about it and still get their bombs if they were power hitters in the first place. (Just ask Bryce Harper, who turned his 2018 season around when he quit worrying about his launch angles just before the All-Star break and got back to putting the bat on the ball. He got his bombs anyway, he drove in his runs anyway, he kept reaching base anyway, and he hit .300 in the second half.)

Here, we’re discussing two hitters who didn’t even think about things like launch angling, and a man who averaged 37 home runs a season versus a man who averaged nine a season gives himself and his team a big advantage on the scoreboard. The advantage is even bigger when the man averaging 37 bombs a year has better teams setting his table, which is exactly what Williams had and Gwynn didn’t when all was said and done.

Maybe if Gwynn could have played most of his career with someone like Rickey Henderson or Wade Boggs hitting ahead of him instead of just the three seasons he had Henderson as a teammate, it would have made a significant difference. Gwynn averaged 76 runs batted in a season but Williams averaged 130. Most of that comes from how much better the Red Sox were in Williams’s prime seasons than after he returned from Korea, of course. Williams averaged far less RBI a season after Korea than before, but he actually still comes out an RBI or two better on average for those seasons than Gwynn does for his entire career.

Traditional stat lovers point to Triple Crowns, and it’s rare enough for a single player to lead his league in batting average, home runs, and RBIs in the same season. It’s only been done seventeen times in major league history, and Williams did it twice, in 1942 and 1947. But let’s ponder the idea of another Triple Crown: leading your league in batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage. If that’s one of your ideas of a Triple Crown, too, then Gwynn’s going to pull up even shorter because he has none but Williams has three such claims, including his staggering claim at age 38 in 1957, sixteen years after his previous claim.

Let’s look at their run production and run creation. If you consider runs produced the sum of runs scored and runs batted in, Gwynn averaged 168 per 162 games . . . but Williams averaged 257 per 162. That’s an 89 run difference in favour of Williams

despite Williams hitting eighteen points lower with runners in scoring position than Gwynn did. But run creation, the formula developed by Bill James, isn’t as simple as who hit more home runs, though the aforementioned litigant seemed to think it did based on a subsequent reply to me. To conjugate run creation you factor all base hits (not just the bombs), walks, intentional walks, sacrifices, double plays, stealing, caught stealing. (You could also throw in how often a player advanced runners on non-sacrificial outs, but tracking that information is a bigger challenge.)

So with all that in the track, the record shows Gwynn created 1,636 runs lifetime and used up 6,661 outs to do it. The record also shows Williams created 2,393 runs lifetime and used up 5,291 outs to do it. By seasonal average, Gwynn created 109 runs to Williams’s 169 runs and used 442 outs to do it to Williams’s 374 outs. Even with only one season’s difference in their careers, that differential is astonishing. Yes, it is to wonder, too, what the three full seasons in his mid-20s lost to military service (he missed part of a fourth likewise but at 33) took away from Williams’s production and creation.

And I didn’t even think about wins above a replacement-level player until now. My aforementioned friend thinks of WAR in terms of the old Edwin Starr soul song:

War! What is it good for? Absolutely nothing! Simplying the definition of FanGraphs, the stat sums up a player’s total contribution to helping his team win. The formulas aren’t standardised just yet, but addressing position players such as Gwynn and Williams you can say it shows you how many more games their teams won

with them than if they’d never existed, by way of their run production, run creation, and what they also contributed to denying the other guys’ scoring.

If the comparison is Gwynn vs. Williams, Gwynn comes out on the short end there, too, alas: his 69.2 lifetime WAR is 53.9 lower. Gwynn was a slightly better defensive outfielder than Williams, but if you were to remove the runs Williams cost his team in the field from the runs he created and produced at the plate, he would still come out ahead by considerable distance. What their WARs mean is that Gwynn’s Padres won 69 more games during his career span

with him than they would have won if he didn’t exist, but that Williams’s Red Sox won 123 more games during his career span

with him than they would have won if he didn’t exist.

My friend saw both players play; I got to see way more of Gwynn at play than I could have seen of Williams, since Williams retired after the 1960 season and I wasn’t even partially aware of baseball at that particular moment. But how can I complain when I’ve seen Henry Aaron, Ernie Banks, Johnny Bench, Barry Bonds, Jim Bunning, Gary Carter, Roberto Clemente, Whitey Ford, Bob Gibson, Vladimir Guerrero, Reggie Jackson, Derek Jeter, Randy Johnson, Sandy Koufax, Greg Maddux, Mickey Mantle, Juan Marichal, Don Mattingly, Willie Mays, Joe Morgan, Eddie Murray, David Ortiz, Cal Ripken, Mariano Rivera, Brooks and Frank Robinson, Tom Seaver, Ozzie Smith, Warren Spahn, and Mike Trout, to name a few?

I can’t complain, either, about getting to see such teams as the 1961 Reds (immortalised in their relief pitcher Jim Brosnan’s

Pennant Race), the 1962 Mets (who

had to be seen to be believed), the 1965-66 Dodgers and Giants, the 1967 Cardinals and Red Sox, the 1969 Mets, the 1970 Orioles, the Big Red Machine, the Bronx Zoo Yankees, the 1979 Pirates, the 1986 Mets, the 1988 Dodgers, the 1989 Woe-rioles, the 1990 Reds, the 1998 Yankees, the 2002 Angels, the 2004 Red Sox, the 2008 Phillies, the 2011 Cardinals, the 2016 Cubs, the 2017 Astros, and last year’s Red Sox.

Only later did I get to read about and see film of Williams’s Comeback Player of the Year final season, including the career-finishing home run immortalised so lyrically by John Updike in “

Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.†And, about Williams’s prickly personality and his seemingly tireless battles with the carnivorous Boston sports press of his time and place. My first real awareness of Williams was

his Hall of Fame induction in 1966, when he wished Willie Mays well after Mays passed him on the all-time home run list. (

He has gone past me, and he’s pushing, and I say to him, “Go get ‘em Willie.â€) And when he called explicitly for some way for the Hall of Fame to honour Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige (

symbols of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given the chance), he touched a nerve that led to the Hall of Fame forming a committee to name and elect the best Negro Leaguers to the Hall.

Those remarks spoke well of Williams, who asked only to be great and willed himself to greatness, who was cocky on the outside but grew up a bundle of awkwardness anywhere else beside a baseball field. And in due course Williams and Gwynn met, and cantankerous Teddy Ballgame took a genuine liking to Mr. Padre, whom he recognised as a fellow hitting student. That speaks very well of Gwynn, whose childhood was as stable as the day was long.

Watching Gwynn he resembled a man who studied every possible nuance and technique of hitting, much the way Williams did. As things turned out, he was once nicknamed Captain Video because not only did he have the habit of studying film of himself like a Biblical scholar, his wife videotaped him at least as often as the Padres did so he could study further. He withstood criticism about his tendency to carry a little too much extra weight, only occasionally letting the hurt show.

He also withstood a rather nasty attack upon him in 1990 when Jack Clark, then a Padre, accused him (and, while he was at it,

tortured pitcher Eric Show) of playing to pad his statistics instead of for the team, and when someone anonymous (Gwynn thought it might have been a teammate, others thought it was a member of the Padres’ grounds crew) left him a Tony Gwynn figurine hung in effigy with arms and legs missing. But Clark was only the most vocal critic of Gwynn’s playing approach. There were others—particularly two of his managers, Dick Williams and Jack McKeon—who said they’d seen few less selfish players in their baseball times.

Strangely enough, in 1990, one criticism leveled toward Gwynn in his clubhouse was that he would bunt with men on base instead of pulling grounders, the better to protect his batting average. Why, the absolute

nerve of the man, assessing a situation, his chance of hitting safely, and deciding his best chance to move runners closer to scoring was to square up and drop a bunt! If someone else did it, even a pure power hitter like Clark, they’d have said

what a guy, taking one for the team. Do we dare ask what those fools would have thought if Gwynn had hit into a double play?

It would have been simple for Gwynn to clock Clark when Jack the Ripper ran into bankruptcy in 1992, thanks to profligate spending and a few dubious legal machinations by part of his legal team. But one of Clark’s first public sympathisers turned out to be Gwynn, who knew only two well what bankruptcy does to a man regardless of how he gets there. Gwynn was there himself in 1987, after his then-agent reneged on loans Gwynn co-signed as a favour, and Gwynn tried but ultimately couldn’t handle the repayments by himself when the banks came calling.

Gwynn once appraised himself this way: “[I’m] a good player . . . but I knew my place. I was not a game-changer. I was not a dominant player.†You can accuse Gwynn of a certain degree of modesty there, but in another sense you can accuse him of being only too self-aware. He was good enough to be a first-ballot Hall of Famer and he didn’t have to be better than that to be one of the game’s genuine all-time greats, a player you loved to watch because he was going to put on a batting clinic that helped his teams win even when most of his teams weren’t as good as he was. And he shakes out as the fourteenth best right fielder who ever played the game. We know how many who didn’t make the top twenty as good as we remember them being?

But Williams at his absolute best

was a game changer and a dominant player. He has in common with Gwynn playing for a lot of teams who went nowhere much otherwise in spite of his best effort and his best deliverance. Williams wasn’t the reason the 1946 Red Sox couldn’t close the deal in the World Series; he wasn’t the reason the Red Sox couldn’t nail the pennant in 1948 (when Joe McCarthy started Denny Galehouse instead of Mel Parnell) and 1949 (when McCarthy lifted Ellis Kinder late in the game when even the Yankees thought he was getting stronger as the game got older, and the Red Sox were down 1-0).

And Gwynn wasn’t the reason the Padres didn’t win the World Series in 1984 and 1998, or a 1996 National League division series, or pulled up just short enough in the National League West in 1989, any more than Williams was the reason the Red Sox collapsed in the 1950s.

That plus their roots, their career longevity, their customary slots in the batting orders, and their Hall of Fame plaques are all they really have in common. Ted Williams reached base more often, produced and created more runs, used far less outs including hitting into far fewer double plays, to give his teams that much better chance to win.

“Ted liked him,†said one eulogist after Gwynn’s death, “and Ted didn’t like anybody.†(Which isn’t

entirely true, if you’ve ever read David Halberstam’s

The Teammates, a chronicle of the sweet lifetime friendship between Williams and Red Sox teammates Dom DiMaggio, Bobby Doerr, and Johnny Pesky.) A year after retiring, Gwynn told an interviewer of one exchange he had with the Splinter:

Once, I was trying to explain to him why hitting the ball out of the ballpark for a hitter like me wasn’t that important. Because if you could handle both sides of the plate, all that matters is when they came in, you hit the ball hard somewhere, then they wouldn’t come in anymore. And he was livid. He said, ‘Major league history’s made on the ball inside.’ It took me two years to figure out what he was talking about. But what he was saying was, when you hit a ball inside out of the ballpark, they don’t come in anymore. And my bread and butter was the ball away. Two years later, when I finally realized what he was talking about, I told him, ‘I have to thank you for giving me that piece of advice that you gave me, because it’s really made a huge difference.’ And he looked at me and just winked. Didn’t say a word, just winked at me.

The exchange must have been at least two years before Gwynn had his single best season for run production. He produced 216 runs, hitting 17 home runs (career high), driving in 119 (also career high), and scoring 97 (ten below his career high). He also created 132 runs, second only to the 143 he created in 1987, the only time he ever led the National League in runs created. Once upon a time, Bob Costas interviewed Williams and Gwynn

together and they delivered an almost professorial dialogue on hitting. At one point, Costas showed a clip of Gwynn finishing a 4-for-4 game against the Phillies by hitting one over the right field fence. On a pitch up and in. Practically up and in his face.

Generations ago, Branch Rickey, otherwise the most nimble mind baseball’s ever known, by then running the Pirates, tried to beat his Hall of Fame slugger Ralph Kiner down in a contract negotiation by comparing Kiner speciously to Babe Ruth. I say “speciously†because Rickey compared Kiner to the Ruthian myth and not the Ruthian facts. Everything Rickey said Ruth could do that Kiner couldn’t was false except for hitting safely more consistently. (They were the same fielder, they were just about the same mostly pull hitter, Kiner was a better baserunner, and

neither Kiner

nor Ruth asked for home ballparks favourable to their hitting strengths.) As Barra said in

Clearing the Bases, “frankly, I think there are a lot worse insults you can dish out for a player than to tell him he finishes second when being compared to Babe Ruth.â€

And there’s likewise a lot worse you can say than to tell Tony Gwynn he finishes well behind Ted Williams. He didn’t have to do more to earn Williams’s respect and even affection, and he didn’t have to do more to earn mine or anyone’s. God rest both their souls in peace, but Mr. Padre wasn’t the only player who finished that far behind Teddy Ballgame.

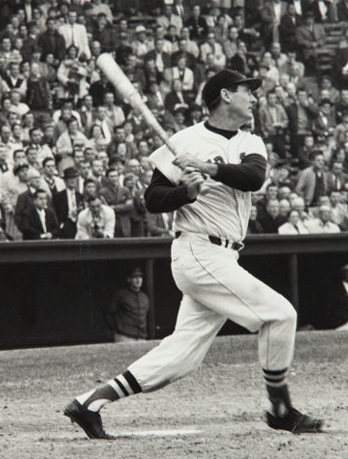

Ted Williams, hitting his final major league home run . . .

Ted Williams, hitting his final major league home run . . .  Tony Gwynn, hitting the only postseason home

Tony Gwynn, hitting the only postseason home

run of his career—a two-run shot in Game One of

the 1998 World Series.-------------------------

@Polly Ticks @Machiavelli @AllThatJazzZ @AmericanaPrime @Applewood @Bigun @catfish1957 @corbe @Cyber Liberty @DCPatriot @dfwgator @Freya @GrouchoTex @Mom MD @musiclady @mystery-ak @Right_in_Virginia @Sanguine @skeeter@Skeptic@Slip18@TomSea @truth_seeker